Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended for diagnostic use. LifeDNA does not provide diagnostic reports on any traits discussed. Genetics is just one piece of the puzzle; please consult a healthcare professional for comprehensive guidance on any health condition.

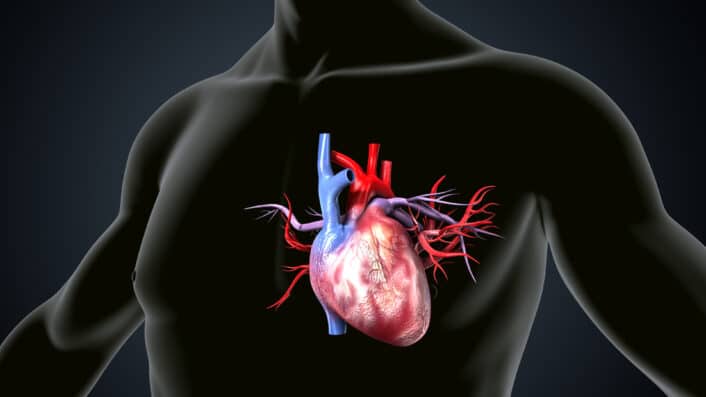

Mitral Valve Prolapse or MVP is a condition where one of the heart’s valves doesn’t close properly. The mitral valve is located between the left atrium and the left ventricle. In MVP, the flaps, also called leaflets, of this valve bulge or prolapse slightly backward into the left atrium when the heart contracts.

For most people, this doesn’t cause any serious health issues. In fact, many people don’t even know they have it until it shows up during a routine check-up. But in some cases, it may lead to complications like mitral regurgitation, when blood leaks backward into the atrium, irregular heartbeats, or rarely, more serious cardiovascular problems.

You may want to read: Unraveling The Genetics of Resting Heart Rate

What Causes Mitral Valve Prolapse?

Mitral valve prolapse or MVP happens when the valve between the heart’s left upper chamber (left atrium) and lower chamber (left ventricle) doesn’t close properly. Instead of closing tightly, the valve’s flaps—called leaflets—become floppy and bulge backward into the upper chamber during a heartbeat. But what causes this to happen? The answer often lies in the structure and strength of connective tissue, which forms the framework of the valve.

The mitral valve is made up of connective tissue that gives it flexibility and strength. Over time, this tissue can become stretched or weakened, which causes the valve leaflets to lose their shape and function. As people age, connective tissues throughout the body—including those in the heart—can gradually break down. This age-related wear and tear can weaken the valve and its supporting structures (like the chordae tendineae), increasing the chances of prolapse.This is especially true in people whose connective tissue is naturally more elastic or prone to damage.

Here are some specific the causes and how they affect the heart:

MVP can be a a result from a mix of genetic factors (see below), physical stress on the heart, and diseases that affect the body’s connective tissues. In many cases, the cause is a combination of inherited tissue characteristics and age-related changes.

Many people with mitral valve prolapse (MVP) don’t notice any symptoms at all. But for those who do, the signs can vary from mild to more bothersome. They may also come and go over time. Here’s a closer look at what some of these symptoms might feel like:

These symptoms can vary from person to person and may not always be linked directly to MVP. However, if you experience them frequently or if they get worse over time, it’s important to talk to your healthcare provider. Keeping track of your symptoms can help guide proper diagnosis and treatment.

Studies suggest that mitral valve prolapse has a genetic component. While MVP can happen on its own, researchers have found that it can run in families, showing that genes play an important role.

One of the earliest signs of a genetic link was seen in families where several members had MVP. Some early cases suggested the condition might be passed down through the X chromosome, but later studies showed that autosomal dominant inheritance is more common. This means that if one parent has the genetic factor linked to MVP, their children have about a 50% chance of inheriting it.

There are different types of MVP based on how the valve tissue is affected. One type called myxomatous MVP, also known as Barlow’s disease, tends to happen in younger people and is strongly linked to inherited gene variants. Another type, called fibroelastic deficiency (FED), usually appears later in life and is more related to aging than genetics.

Several genes have been identified in relation to MVP, some playing a role especially in families with inherited forms. These include:

However, these rare genetic mutations only explain a small portion of MVP cases. Most people with MVP likely have common genetic variants, SNPs, which are tiny changes in their DNA that each slightly raise their risk of developing the condition. These were discovered through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), a type of research that looks at the entire genome to find patterns linked to disease.

What is interesting is that some family members may not show full-blown MVP, but instead may have early or subtle signs, like slight changes in valve structure. These early signs may still be genetically influenced and may develop into full MVP over time. In fact, studies have shown that children are more likely to develop MVP if their parents have even mild valve changes.

Researchers also think there may be a genetic link between MVP and other heart problems, such as ventricular arrhythmia or certain forms of cardiomyopathy. This suggests that MVP may be a part of a bigger genetic pattern affecting the heart’s structure and rhythm.

To understand these connections better, scientists use animal models. These models are bred to carry the same genetic changes found in humans with MVP. Studying how these changes affect heart structure and function helps researchers uncover the underlying causes and possible ways to treat or prevent MVP. Genetics plays a major role in MVP, especially in cases that run in families or appear at a young age. Both rare mutations and more common genetic traits contribute to how and when MVP develops. Recognizing this genetic connection is key to improving diagnosis, guiding family screening, and eventually finding better treatments.

How Is Mitral Valve Prolapse Diagnosed?

Mitral Valve Prolapse is often discovered during a routine physical exam. Your doctor might hear a distinctive clicking sound or murmur with a stethoscope, which can lead to further tests. If mitral valve prolapse or MVP is suspected, your doctor may order several tests to confirm the diagnosis and understand how well your heart is functioning. These tests can provide a clearer picture of your heart’s structure and rhythm. Common diagnostic tools include:

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is usually not dangerous. Most people with this condition live normal, healthy lives without any serious problems. However, in some cases, MVP can lead to complications—especially if the valve’s flaps are more severely affected. The most common complication is mitral regurgitation, which happens when the valve doesn’t close properly and allows blood to leak backward into the upper chamber of the heart. This leakage can put extra strain on the heart and may cause symptoms like tiredness, shortness of breath, or reduced ability to exercise.

Another possible complication is arrhythmia, which means the heart beats irregularly. Some people may feel heart palpitations, fluttering, or even dizziness. While most arrhythmias are harmless, some may require treatment. A rare but serious risk is endocarditis, an infection of the heart’s inner lining or valves. People with damaged valves are more likely to develop this infection, which can be life-threatening and usually requires strong antibiotics or even surgery. In very rare cases, severe mitral valve damage can lead to heart failure. This happens when the heart can no longer pump blood effectively. Regular checkups and early treatment can help prevent these complications and keep the heart working well.

For many, it’s a manageable condition that doesn’t interfere with daily life. However, if you experience symptoms or are at higher risk of complications, there are several ways to take care of your heart and improve your quality of life.