How Genetics May Influence Friendship Satisfaction

Aira

on

May 8, 2024

What is Friendship Satisfaction?

Friendship satisfaction refers to a person’s perception of the overall quality of their relationships with friends. It is an important indicator of a person’s subjective well-being, as friendships serve many important functions in a person’s life, such as providing companionship, help, intimacy, reliable alliance, self-validation, and emotional security.

Research on friendship satisfaction can be broadly classified into two categories:

- Identifying the predictors of friendship satisfaction. The social provision perspective suggests that the level of satisfaction with friendships is determined by the extent to which they fulfill the various needs of an individual.

- Examining the outcomes of friendship satisfaction. Studies have found that strong, high-quality friendships are associated with higher life satisfaction, even for people who are dissatisfied with their romantic relationships.

Friendship satisfaction has also been linked to lower levels of depression, anxiety, and hostility, as well as higher self-esteem and psychosocial adjustment.

Signs of Friendship Satisfaction

The key signs of friendship satisfaction involve a sense of mutual care, trust, intimacy, and fulfillment in the relationship, rather than it being one-sided or convenience-based.

- Mutual support and reciprocity: Satisfied friendships involve a balance of giving and receiving support, where both friends make efforts to help each other when needed.

- Open communication and emotional intimacy: Satisfied friends feel comfortable sharing their thoughts, feelings, and personal information with each other. They listen with empathy and don’t dominate the conversation.

- Shared interests and enjoyment of each other’s company: Satisfied friends have common hobbies, activities, or interests that they can bond over and genuinely enjoy spending time together.

- Reliability and dependability: Satisfied friends can count on each other and trust that their friends will follow through on plans and be there for them. They don’t frequently cancel or forget plans.

- Mutual respect and consideration: Satisfied friends respect each other’s opinions, priorities, and boundaries. They consider each other’s needs and preferences when making decisions.

- Absence of one-sided or exploitative behavior: In satisfied friendships, neither friend takes advantage of the other or expects them to be constantly available to fulfill their needs. The relationship is balanced.

The Genetics of Friendship Satisfaction

Recently, research studies have found that genetics can be a major factor in friendships.

A 2022 GWAS that studied more than 269,000 individuals of white British ancestry found genetic variants associated specifically with friendship satisfaction.

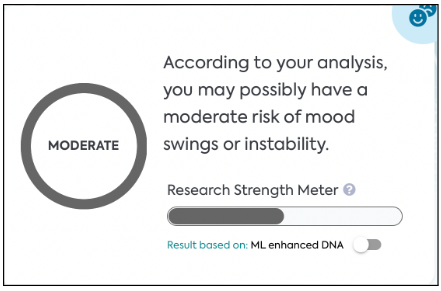

While individual genes and genetic variants in specific genes could be associated with a person’s level of satisfaction in friendships, another approach for determining a person’s genetic likelihood for a trait is to use a PRS (Polygenic Risk Score), which comes from a combination of multiple SNPs that together play a role in the genetic association. LifeDNA’s high-density SNP signature for the Friendship Satisfaction Trait has been developed from a set of 659 SNPs that together play a role in fluid intelligence (note: only 15 top SNPs are displayed on our report).

Genetic variants in some interesting genes were found to be associated with friendship satisfaction. These include SEMA6A (rs563598) and SEMA6B (rs32972). These two genes encode for different members of a large family of Semaphorins, which include both secreted and membrane-associated proteins, many of which have been implicated to have important roles in neuronal growth processes in the brain.

Non-Genetic Factors Influencing Friendship Satisfaction

Factors influencing friendship satisfaction can be diverse and multifaceted, encompassing various aspects of the relationship dynamics. Based on the provided sources, some key factors that influence friendship satisfaction include:

- Communication and Self-Disclosure: Effective communication and the ability to share thoughts, feelings, and personal information openly contribute to friendship satisfaction. Mutual self-disclosure fosters intimacy and trust in friendships.

- Similarity and Shared Interests: Having common values, interests, and aspirations with a friend can enhance satisfaction in the relationship. Shared experiences and activities create a sense of connection and enjoyment.

- Reciprocity and Mutual Interest: Friendships characterized by reciprocal candor, mutual interest, and personableness, where both friends show genuine interest in each other and reciprocate kindness and sincerity, tend to be more satisfying.

- Physical Attraction and Attractiveness: While not the sole determinant, physical attraction, and perceived attractiveness can influence friendship chemistry and satisfaction.

- Parental Relationships and Emotional Regulation: The quality of parental relationships, especially with the mother, and the ability to regulate emotions play a significant role in predicting satisfaction with friendship networks. Conflict between parents can also impact friendship satisfaction.

- Individual Factors like Shyness, Self-Esteem, and Social Skills: Personal characteristics such as shyness, self-esteem, social skills, and defensive pessimism can affect the formation and quality of friendships, thereby influencing satisfaction levels.

How to Improve Friendship Satisfaction

Friendship satisfaction requires effort from both sides. It is possible to cultivate deeper and more satisfying friendships. To increase your friendship satisfaction, consider the following tips:

- Foster open and honest communication with your friends. Share your thoughts, feelings, and needs, and encourage them to do the same. Effective communication helps build understanding, resolve conflicts, and strengthen the bond between friends.

- Handle conflicts constructively and address any issues that arise. Approach disagreements with empathy, active listening, and a willingness to find a resolution that satisfies both parties.

- Prioritize spending quality time together. Engage in activities you both enjoy, have meaningful conversations, and create shared experiences.

- Invest time and effort in maintaining and nurturing the friendship. Reach out regularly, make plans to meet, and show interest in their lives.

- Manage your expectations. Recognize that no friendship is perfect. Focus on appreciating the positive aspects of the friendship rather than dwelling on minor shortcomings

The LifeDNA Personality & Cognition Report

In a world where understanding ourselves is crucial for meaningful connections, the LifeDNA Personality & Cognition Report offers an invaluable tool for enhancing your connection with yourself and others – including friendship satisfaction. By diving deep into your unique personality traits and cognitive strengths, this report provides personalized insights that can revolutionize your way of knowing yourself better and your approach to relationships.

Armed with a deeper understanding of your communication style, emotional triggers, and conflict resolution strategies, you’ll be better equipped to navigate social dynamics and foster deeper connections with others. Get your report today!

You may also like: Does Your Genetics Influence Your Social Life?

Summary

- Friendship satisfaction refers to how someone perceives the quality of their friendships, which greatly influences their well-being. It involves feelings of companionship, support, intimacy, and emotional security.

- Friendship satisfaction is characterized by mutual support, open communication, shared interests, reliability, respect, and the absence of exploitation or one-sided behavior.

- While genetics can play a role in personality traits that affect friendships, non-genetic factors like communication, shared interests, reciprocity, physical attraction, parental relationships, and other individual traits also significantly influence friendship satisfaction.

- Improving friendship satisfaction involves fostering open communication, handling conflicts constructively, spending quality time together, investing in the relationship, and managing expectations. It requires effort from both parties to nurture and maintain fulfilling friendships.

References

- https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1090

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10902-022-00502-9

- https://www.healthline.com/health/beware-the-one-sided-friendship

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10086127/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4470381/

- https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3118&context=etd

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jpr.12201

*Understanding your genetics can offer valuable insights into your well-being, but it is not deterministic. Your traits can be influenced by the complex interplay involving nature, lifestyle, family history, and others.

Our reports have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The contents on our website and our reports are for informational purposes only, and are not intended to diagnose any medical condition, replace the advice of a healthcare professional, or provide any medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Consult with a healthcare professional before making any major lifestyle changes or if you have any other concerns about your results. The testimonials featured may have used more than one LifeDNA or LifeDNA vendors’ product or reports.